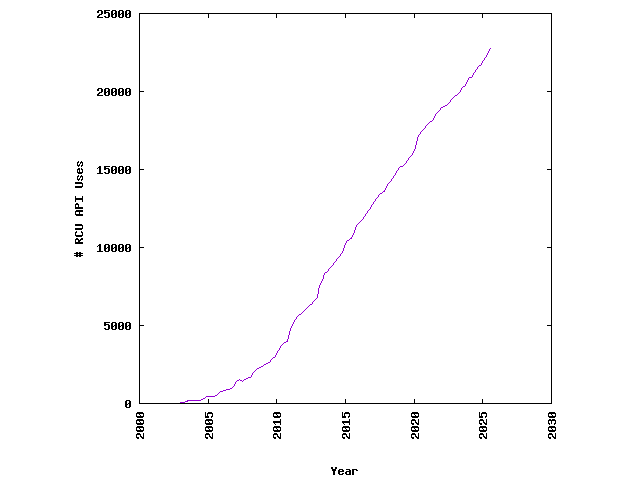

The best summary of Linux RCU usage is graphical:

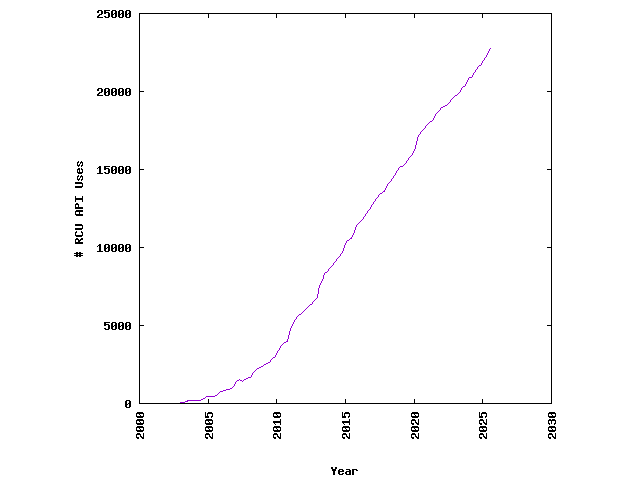

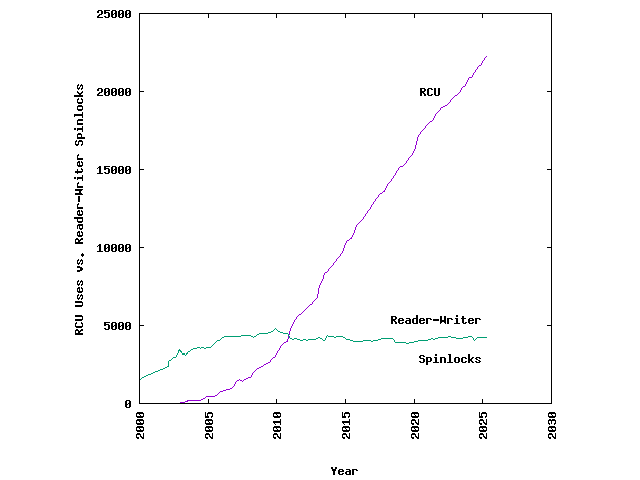

However, the above plot might give a too-prominent impression of RCU's usage in the Linux kernel. It is more even-handed to compare RCU usage to the combination of that of spinlocks and semaphores, both exclusive and reader-writer variants, as shown below:

Here, the traces for RCU don't rise so far off of the x-axis. Furthermore, the rate of usage of RCU (in absolute terms) is growing more slowly than that of locking. Lastly, the trace for locking is conservative, since it counts only the main locking primitives themselves, and not the “wrapper” macros that are commonly used throughout the kernel. (That said, RCU is now gaining a considerable number of wrappers as well, and these are not counted, either.)

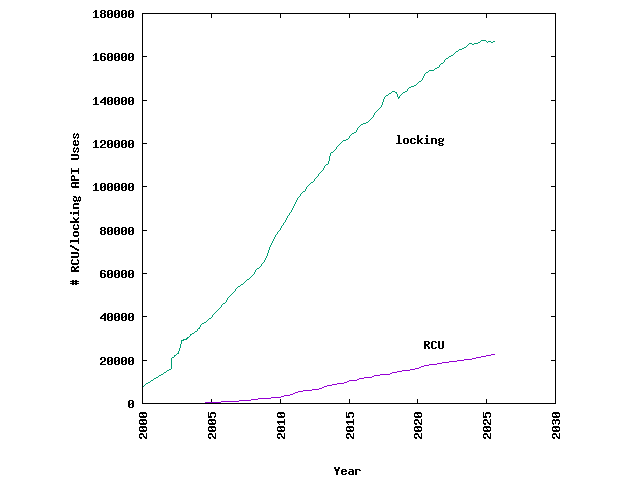

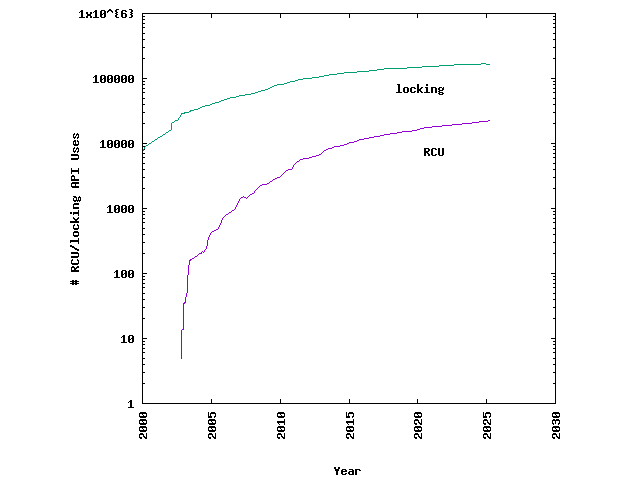

Finally, in order to pull RCU a bit further off of the x-axis, the next figure shows this same data on a semi-log plot:

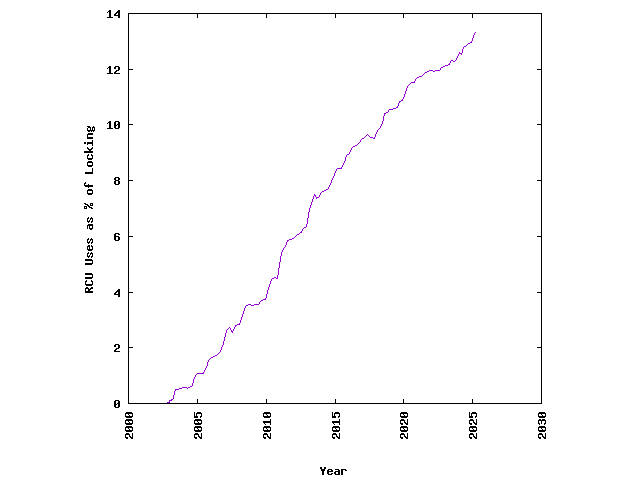

Here we can see that the percent rate of growth of RCU has exceeded that of the other locking primitives, so that as of late 2004, the use of RCU rose to within two orders of magnitude of that of normal locking, and within one order of magnitude in 2018. RCU usage now exceeds 10% that of locking, as can be seen in the following figure:

However, please note that I do not expect RCU's usage to ever come close to that of the combined locking primitives. For one thing, the rate of RCU's growth has in fact been decreasing, approaching that of the other primitives. Furthermore, the absolute level of RCU usage does decrease sometimes, for example, during netfilter consolidation in 2.6.22 in mid-2007. This is to be expected: After all, RCU is a specialized primitive, and it is exceedingly important to use the right tool for the job. For a great many jobs, normal locking remains the best tool. Finally, almost all RCU uses in the Linux kernel use locking to protect updates, which does place a hard upper limit on RCU's fraction of synchronization primitives.

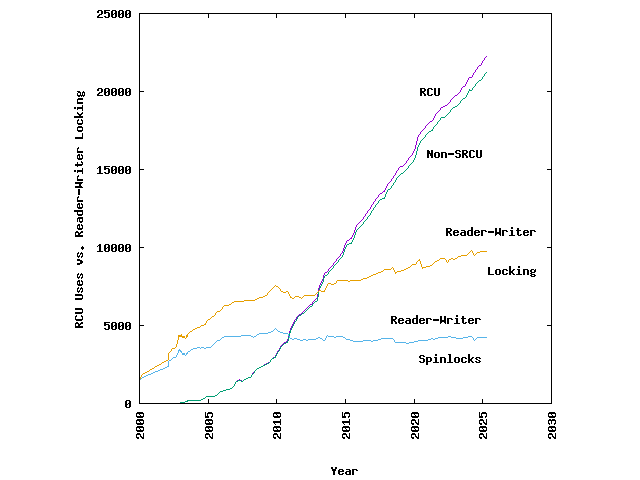

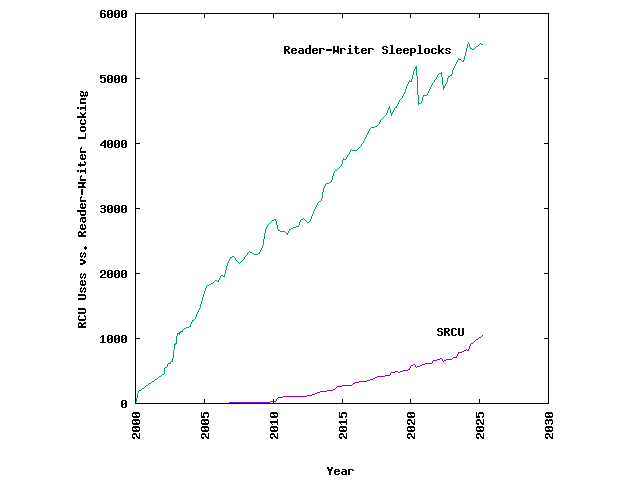

However, as you can see in the plot below, experience indicates that RCU is significantly more heavily used in the Linux kernel than is reader-writer locking. So, yes, RCU is specialized, but perhaps quite a bit less specialized than is reader-writer locking, courtesy of RCU's read-side performance and scalability.

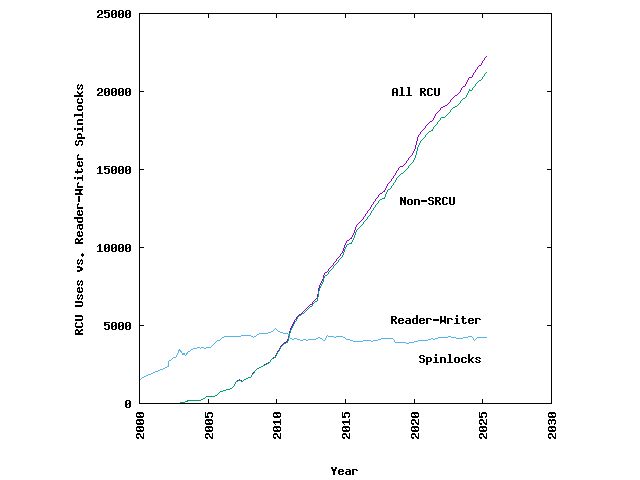

Note that the above plot compares all RCU API uses to only reader-writer spinlocks, excluding reader-writer sleeplocks. For quite some time, this made sense because SRCU (“Sleepable RCU”) did not exist until 2006, and was not used heavily for many years after that. And it is still not used all that heavily compared to vanilla RCU, but as of 2025, SRCU has more than 1,000 uses of its API in the Linux kernel, as shown by the gap between the upper pair of traces:

Although we can say with confidence that RCU is more than four times more heavily used in the Linux kernel than are reader-writer spinlocks, it still makes sense to also include reader-writer sleeplocks, shown by the gap between the lower pair of traces:

It also makes sense to compare SRCU to reader-writer sleeplocks:

Although the SRCU trace is easily distinguished from the x-axis, it is far below that of reader-writer sleeplocks.

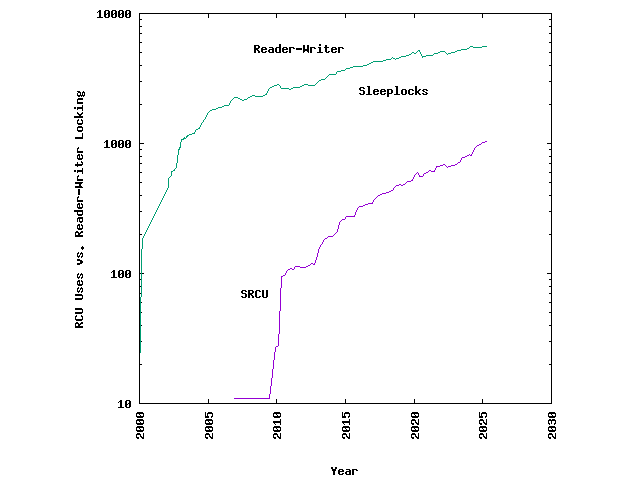

On the other hand, this semi-log plot shows the relative rates of growth more clearly:

SRCU usage is increasing faster than that of reader-writer sleeplocks, and first came within an order of magnitude in 2018.

However, SRCU usage has grown quite a bit more slowly than that of RCU. For example, RCU usage grew by more than a factor of 50 during the ten years after it passed 100 uses. In contrast, SRCU usage grew by less than a factor of 6 during the ten years after it passed 100 uses. On possible reason for the slower growth of SRCU is that the critical sections for reader-writer sleeplocks tend to be heavier weight than those of reader-writer spinlocks, which tends to make RCU's performance advantages more attractive for spinlocks than SRCU's for sleeplocks.

The raw data for these plots are available here and on kernel.org. The scripts that produced this data from kernel.org are available (under GPL) here.